Salvage Job

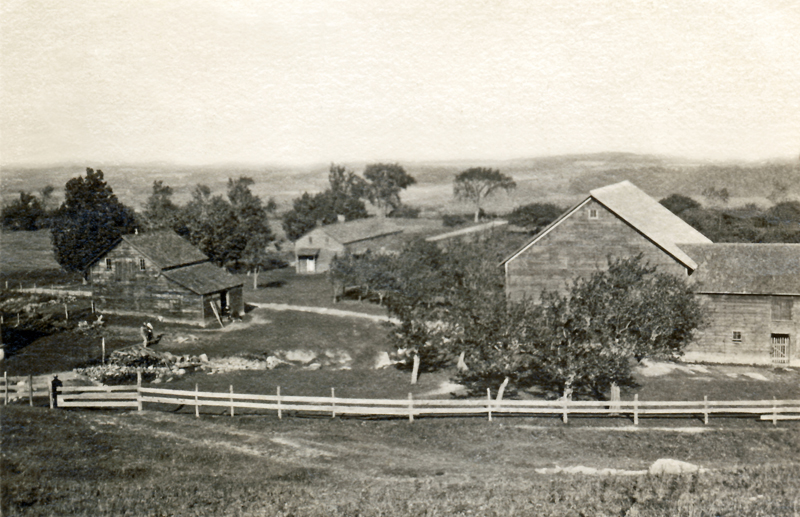

Architect reclaims a graceful old barn on a 19th-century farmstead

By Paul Grondahl, Albany Times Union

New Scotland

In 1981, Bob Mitchell bought a 2-acre farmstead at the base of the Helderberg Mountains near Thacher State Park for $20,000.

He outbid a guy who wanted to use the land for a junkyard.

The price was low because it was assumed the buyer would have to pay to demolish a decrepit 1804 farmhouse that had no electricity and no indoor plumbing, along with two tumbledown barns that dated from before the Civil War.

Mitchell, an architect who salvages structures others consider lost causes, saw something worth reclaiming in the sturdy old bones of the neglected buildings that been in the Winne family for many generations. Mitchell became only the second owner in two centuries of a farm that featured an apple orchard, hayfields and livestock.

Mitchell was enamored of the stout timbers and graceful mortise-and-tenon joints of the large 1830s-era barn with hay loft, box stalls for sheep, cow stanchions and hitches for horses.

Mitchell and his former wife, pregnant with their first child, began restoring the farmhouse during a bitterly cold winter. After four months of frantic work that included gutting the interior down to the studs, installing a heating and electrical system, adding a bathroom and tearing down walls to expand the kitchen, the couple moved in that spring.

They hauled lumber and building materials with a 1969 Volkswagen squareback station wagon, a $200 workhorse. “We were young and probably a little crazy to move in after four months,” recalled Mitchell. “We weren’t afraid of hard work and sweat equity.”

He is the type of fellow who rarely makes a trip to the dump without bringing something home.

Over the course of three decades, Mitchell has turned the property and four-bedroom, 2,700-sqare-foot farmhouse into a solar-powered showcase of country living. They used antique tools for the finish work. “It never really ends. We’re always doing something,” he said.

The most recent project was converting part of the large barn into office space for his firm, Mitchell Associates Architects, which has five employees. They specialize in designing fire stations and public safety buildings. They have done more than 110 fire station projects — additions, renovations and new construction — across the Capital Region, and from Nantucket to Alaska.

The business had outgrown the dining room, and the timing merged with a long-held desire of restoring the barn. The biggest challenge of moving his office 50 yards from farmhouse to barn was not related to construction issues. The town’s planning board and a lengthy zoning variance application consumed 18 months and extensive research of the “home occupation in accessory structure” provision.

“It’s ironic that a lot of people are wringing their hands that so many barns are falling down in town, after I had such a hard time,” he said. “If they don’t make it easier to save barns, we won’t have any barns in this town in 50 years.”

Without the considerable effort and expense of adaptive reuse, Mitchell figures he would have written the obituary for his barn by now, too.

He frequently pulls over and scrutinizes old barns while driving around the sprawling, rural town of New Scotland. He’s made an informal inventory over the past three decades and has sadly watched the demise of many barns. He saw some torn down because they were so far gone from neglect that they were unsafe. Others were dismantled and the timbers shipped to other states to be used in high-end custom homes.

Mitchell, his son and daughter did much of the barn renovation and construction themselves, including graceful landscaping and building a bridge over a nameless stream that gently burbles a few yards behind their office.

In August 2011, one week after they moved in, Tropical Storm Irene turned the little stream into a raging torrent of floodwater, mud, debris and rocks. The flooding began rising several inches up the side of the barn.

“I was freaking out,” Mitchell said. When the flooding receded, he dreaded going inside and feared their brand-new office was ruined.

“We used spray-foam insulation and it kept the water out. It saved our office from Irene,” Mitchell said. He spoke from a bright, airy office with a view of open fields. His computer sits on the spot where horses once clomped across a dirt-floored pen.

Mitchell is a 65-year-old unreconstructed hippie. After earning a bachelor’s degree in architecture from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, he became an activist and community organizer in Troy in the late-1960s.

In the summer of 1968, Mitchell lived in a remote cabin on RPI-owned land within Grafton Lakes State Park. His nearest neighbor was a 1-mile hike through the woods. That neighbor was Granville Hicks, the writer and Marxist literary critic who once taught at RPI and immortalized Grafton in his book, “Small Town.” Hicks and his wife, Dorothy, frequently invited Mitchell to dinner, where he met Bernard Malamud and other literary figures.

Mitchell, a native of New York City, lived in a geodesic dome he built on a small spit of land in the Poestenkill Creek in Troy in the early 1970s. It was accessible by a small suspension bridge he constructed. “All I had in the dome was a waterbed, an Oriental rug and a box of granola,” he recalled.

He’s always been a seeker and student of philosophy. For years, he designed solar additions and homes. “Back in the day, we thought we were going to change the world,” he said with a rueful chuckle.

As Mitchell gave a tour of the converted barn, he was shadowed by a black Labrador retriever, a stray that had been hit by a car. They nursed the dog back to health and named him Oliver.

“After Oliver Twist, the orphan,” Mitchell said.

He’s now the office dog, a rescue, apropos for an old barn that was almost lost.